Built to Betray: Economies and Their Limitations

underline

One of the most perplexing aspects of social organization is the role that economic and financial institutions play within it. This post aims to challenge the perception that these institutions are self-organizing systems in their own right, and instead reframe their actual function: sustaining energy transfers between social subsystems and the physical environments that support them. To explore this, I will focus on the energy-to-work function in open dynamical systems—specifically, how each subsystem relies on developing a structured strategy for converting energy into work in order to regulate its operations and resist entropy over time.

This post will highlight the physical constraint of continuous growth in complexity, which every open dynamical system must confront to remain open and far from equilibrium. I wish to offer this conceptual framework to highlight the need to focus attention on societal boundaries as a prerequisite for developing economic and financial institutions. In other words, this post stresses the need for a planetary transition—from a collection of nation-states to a more cohesive, flock-like humanity that parametrizes the wealth and well-being of all living systems.

In This Downward Course

underline

Living systems are unique in their ability to construct bounded niches that locally defy the second law of thermodynamics. By converting energy into work, they resist the universe’s deterministic drift toward increasing randomness and disorder. Work, in this context, serves two essential functions. First, it reduces the metabolic “price” a system must pay to maintain order. Second, it creates and sustains order controlling the range of acceptable actions and behaviors within the system.

In social systems, subsystems use energy to regulate internal activities and to construct and maintain boundary conditions—both between themselves and with their surrounding environment. Families, for instance, reduce the cost of care by maintaining clear boundaries (in today’s world, often through legal registration), limiting the range of legitimate behaviors (e.g., prohibiting adultery or incest), and distributing caregiving responsibilities among members. Issues such as children’s rights or gender equality reveal that care responsibilities are not governed by immutable rules, but are continually shaped through sociopolitical negotiation.

Nation-states, to take another example, reduce the cost of establishing and maintaining permanent settlements by monopolizing the use of force and developing strategies to legitimize that monopoly. This ensures social order and predictable environments—and, by extension, the continued funding and operation of state apparatuses. While much attention is directed toward the free market and capitalist framework, it is crucial to recognize that a nation-state canfunction without a free market, but not the other way around.

end of box

Energy

underline

The vitality of open systems—their capacity to adapt over time—depends on their ability to source energy from their environment, convert it into usable forms, and dispose of residual “heat” or materials that can no longer be stored or repurposed. The economy of our bodies offers a compelling example of how open systems depend on their living environments. The dramatic changes in our physical surroundings provide another example, drawing attention to the boundaries and economies of other self-organizing systems, such as oceans and rain forests. From this perspective, we can hypothesize that our survival depends not only on our own economic procedures, but also on the ability of other self-organizing systems to regulate and manage theirs.

Beyond the continuous processing of energy and disposal of waste, a system’s energy needs grow in tandem with its increasing complexity. The level of complexity depends both on the arrow of time—that is, how long a system has existed—and on its temporal depth of planning, or how far into the future it projects. For example, while infant development has remained relatively stable across cultures and history, fertility rates, age at first pregnancy, and life expectancy have shifted dramatically in some societies as a function of their growing complexity.

Societies that oscillate between stagnation and chaos tend to experience limited growth in complexity, compared to adaptive societies that plan further ahead. These latter systems must develop strategies not only for survival, but also for managing the costs associated with increasing complexity. As complexity grows, adaptive systems must meet higher energy demands—either by discovering new energy sources or by using existing ones more efficiently, thereby reducing heat.

Moreover, as adaptive systems expand, their impact on the environment intensifies. To remain sustainable, their boundaries must extend to include more of the environment as part of the system itself. In other words, creating systems that are more efficient and less wasteful requires internalizing parameters that were previously considered “external.”

Returning to the human example: taking medication to help the body regulate its functions, hiring caregivers to support family life, or developing a family business are all strategies through which families manage growing complexity—by integrating more of their surrounding environment into their own familial system.

Work

underline

The primary function of economies and financial institutions is to calculate and organize the costs associated with sustaining life at a societal scale. These include metabolic costs and regulatory costs. Metabolic costs refer to the conversion of primary energy sources into secondary forms that the system can deploy to perform work, as well as the disposal of waste. Regulatory costs, on the other hand, can be compared to allostatic regulation—the process by which an organism maintains stability through change, adapting its internal systems in anticipation of and response to environmental demands. Yet both metabolic and regulatory costs are shaped by the boundary conditions of the subsystem they help sustain.

This means that economies do not reflect the actual state of the environment in which a society is embedded. Much like sensory data, economic and financial metrics help us assess the accuracy of our models of the environment, based on the prediction errors they reveal. Economic institutions are designed to minimize these errors, but they cannot self-correct or self-organize—just as our senses of sight or hearing cannot revise our internal models. They merely signal how accurate those models are in light of the data.

In other words, we can either adjust our models to better predict the data, or we can reduce the salience of the data to preserve the predictive power of our existing models. This means that both proving and denying climate change can serve as strategies for sustaining the economic models of nation-states, though they differ significantly in their adaptive value. The expectation that economic models and institutions will adapt in response to new data reflects an implicit assumption: that economies are inherently self-organizing and responsive to environmental change. In reality, the systems capable of self-organization are our societies and the environments in which they are embedded. And while earlier methods of energy production sustained the development of two social subsystems within each energy regime, the current nation-state model is exploiting Earth's reserves at such a pace that our most viable path forward is to redefine the boundary conditions of our societies—namely, to move beyond the framework of nation-states toward a new form of social organization that can parameterize and make sense of data currently ignored, whether willfully or not.

end of box

New Boundary Conditions – New Economies

underline

Throughout history, societies have relied on a few primary energy sources, but our abilityto extract and channel them into social systems has evolved dramatically—fundamentally reshaping the planet in the process. Broadly, three distinct energy regimes can be identified, each differing in magnitude and scale. The foraging regime, corresponding to the socially constructed subsystems of families and tribes, marked by the intentional use of fire. The agrarian regime, corresponding to the socially constructed subsystems of nations and religions, marked by the intentional reproduction of biomass flows. The industrial regime, corresponding to the socially constructed subsystem of nation-states, marked by the intentional use of fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas).

While the differences in magnitude and scale among these regimes are clear, they sharetwo essential properties. First, the construction of the social subsystem has always preceded the development of each energy regime. In other words, we do not accidentally discover new methods of extracting energy from the environment; rather, we construct social systems that enable experimentation with new modes of energy extraction—modes that then become defining features of our relationship with the environment.

Second, all energy regimes to date have focused on identifying and exploiting energy sources, while giving far less consideration to issues of waste and energy sufficiency. Our societies have expanded the means of energy extraction, but rarely the means of maintaining balance within the systems that depend on them.

What's next?

underline

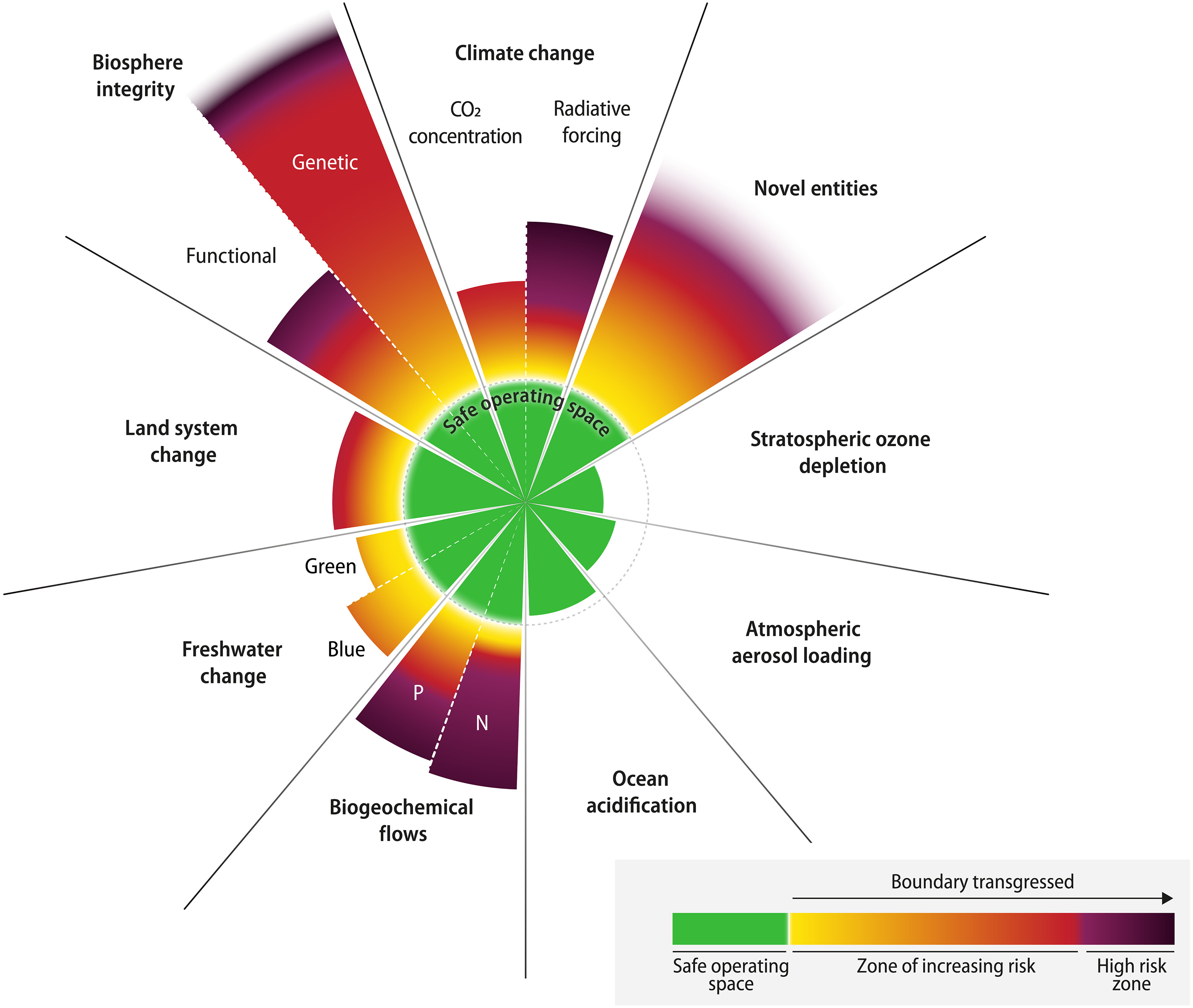

I hope the framework I lay out here will offer a clearer conceptual pathway for modeling the metabolic and regulatory costs of our emerging society. In terms of metabolic costs, since our current economic and financial institutions have contributed to the destabilization of nearly all living systems, the boundaries of future societal models must include and parameterize these systems as integral parts of the economy. Put differently, our newly constructed society must encompass the metabolic costs of the living systems that sustain us—meshing environment and society into a unified energy-to-work framework. This requires uncovering the causal structure of living systems—their dynamic, self-organizing, self-correcting regions—so that energy-to-work metrics become minimal and highly synergistic, reducing waste to nature’s levels.

On the regulatory side—often embodied by financial institutions or so-called “free” markets—regulation should be oriented toward profit in the sense of “future.” That is, the regulatory costs of our economies should provide effective methods for evaluating how much time an economic activity adds to or subtracts from our collective future. This would allow us not only to identify which activities are wasteful or harmful, but more importantly, to prioritize and profit of those that “buy us more time” on the planet.

Again, just as we had to transition from monarchies and gods to nation-states to unleash the industrial age, we cannot build a future-oriented economy within the confines of profit understood merely as margin on investment.

This for three main reasons: first, the feedback loop of nation-states—an essential condition for developing capitalist economies—is extremely costly. Their dependence on cheap energy resources leads deterministically to a lock-in between nation-states and economic models that externalize most energy costs. Put simply, nation-states must protect their citizens at all costs, and placing limits on energy extraction risks societal collapse. Indeed, some societies are already struggling to maintain access to energy, teetering on the brink of collapse.

Second, in attempts to provide short-term solutions to economic crises, nation-states often manipulate the very boundary conditions they work so hard to construct and maintain. Examples include deploying armed forces against civilian populations, denaturalizing or displacing citizens, and relying on mobile foreign populations to mitigate labor shortages and surpluses. While some may defend the necessity of these policies, they are economically driven actions that undermine the logic of social boundaries and are likely, at least to some extent, to erode societal cohesion. Ultimately, the metabolic cost of maintaining porous boundaries increases in the same way that leaving a refrigerator door open raises your electricity bill.

Third, as mentioned above, nation-states are affected by many factors that are not parameterized in their predictive models—from pollution and biodiversity to extreme weather events. Even the fact that nation-states are no longer dependent on legitimacy granted by their citizens underscores the urgency of formulating new boundary conditions and transitioning legitimacy from nation-states to a new system. Without such a shift, it is only a matter of time before our societies succumb to the second law of thermodynamics.

end of box

From Economies to Ecologies

underline

To sum up, new economic and financial systems are not simply a matter of technological innovation, new energy resources, or alternative currencies. They hinge on one invaluable process: reducing our commitment to existing forms of self-organization—both in terms of targets and social rules—and redirecting that commitment toward new organizational forms. These new forms should expand the pool of risk-takers and risk-sharers, and incorporate more, not fewer, environmental parameters into their predictive models.

We must seek out forms of self-organization that make sense of people currently regarded aspoor, marginalized, or underrepresented. We must look for niche constructions that depend on deeper alignment than what our present civilizations offer. We must identify self-organizing activities that regulate the state through legal precedent, Supreme Court rulings, or discursive decisions made by nation-staterole holders.

I call these forms of self-organization consensus-networks, and evidence of their superior ability to predict and respond to the living environment dates back to the abolitionist movement. Structurally, these networks achieve more with less for several reasons. First, they use consensus as a feedback loop—non-violent and non-coercive. The boundaries of these networks are inferred through alignment between values and actions. Moreover, network structures are defined by relationships, not territory or identity. Like a flock or a mycelium, their modality allows for shape-shifting boundaries, enabling collaboration while severing ties with harmful actors—without risking collapse or losing coherence.

Additionally, networks can increase the number and redundancy of data points, allowing knowledge production to emerge from consensus rather than monopolized control. Each member acts as a data transmitter—able to upload, scan, review, and process information at a fraction of the cost of a government employee. In this way, networks can evolve into knowledge hubs, reducing the cost of data collection, closing existing data gaps, and enhancing the legitimacy of knowledge production by grounding validity and reliability in consensus mechanisms.

Finally, consensus-networks can use attention as a tool to shape new mechanisms of risk-sharing and risk-taking—transforming our roles as citizens and economic actors into stewards of the planet’s living systems. This new perception of self and other will empower us to guide technological development in service of our newly discovered role and identity, and away from models that leave us increasingly powerless and justifiably discontent.