The edge of chaos

underline

Self-organizing systems depend on their ability to maintain effective separation from the environments in which they exist. At the sociopolitical level, this requires not only the ability to distinguish order from chaos, but more importantly, the ability to detect the sources of surprise or uncertainty within the system itself. This will be the focus of this post. I’ll illustrate how tools designed to create order can become sources of disorder and trace the morphism from borders to boundaries. I’ll begin with borders because, although they are a relatively recent phenomenon, their influence on shaping our sociopolitical environment warrants a closer examination of their function and limitations.

Borders refer to a politically or legally defined separation between two (or more) geographical or administrative entities, such as municipalities, states, or countries. Within these bordered entities, the development of property laws introduced another use of borders: demarcating legally enforceable separation between public or national territories and privately owned land and property.

Borders are formal, enforceable, and often visible. Internally, they are used to administer laws and policies, manage resource use, and maintain order by excluding so-called 'rough' actors. Externally, borders serve to identify and regulate the movement of agents, protect against external invasion, and manage external pressures by raising or lowering barriers to territorial crossings.

The main limitation of borders is that they derive their logic and power from the entities that enforce them. In other words, if the system’s logic is accepted by agents both within and beyond it, borders become redundant. If enforcement is required to maintain a border, that border will persist only as long as the system upholding it can continue to do so.

Thus, borders reveal the boundaries of a self-organizing system and highlight the limits of its internal logic—that is, how much of the environment can be organized by the system’s own reasoning or structure (its “self”).

end of box

Boundaries

underline

The boundaries of social systems function more like a negative feedback loop than a fixed separation in time and space. They indicate the extent to which a system’s logic can persist as a distinct and autonomous self, and its ability to endure under changing conditions.

The boundaries of all nation-states—democratic or otherwise—are defined by the limits of their legitimacy to use force. In other words, regardless of their formal borders, nation-states can extend their boundaries as long as they retain legitimate authority to use force. This legitimacy can be exercised not only through legal systems, but also through economic means or military power. Conversely, when a nation-state struggles to maintain its monopoly on force, it will also struggle to uphold its logic within its own borders.

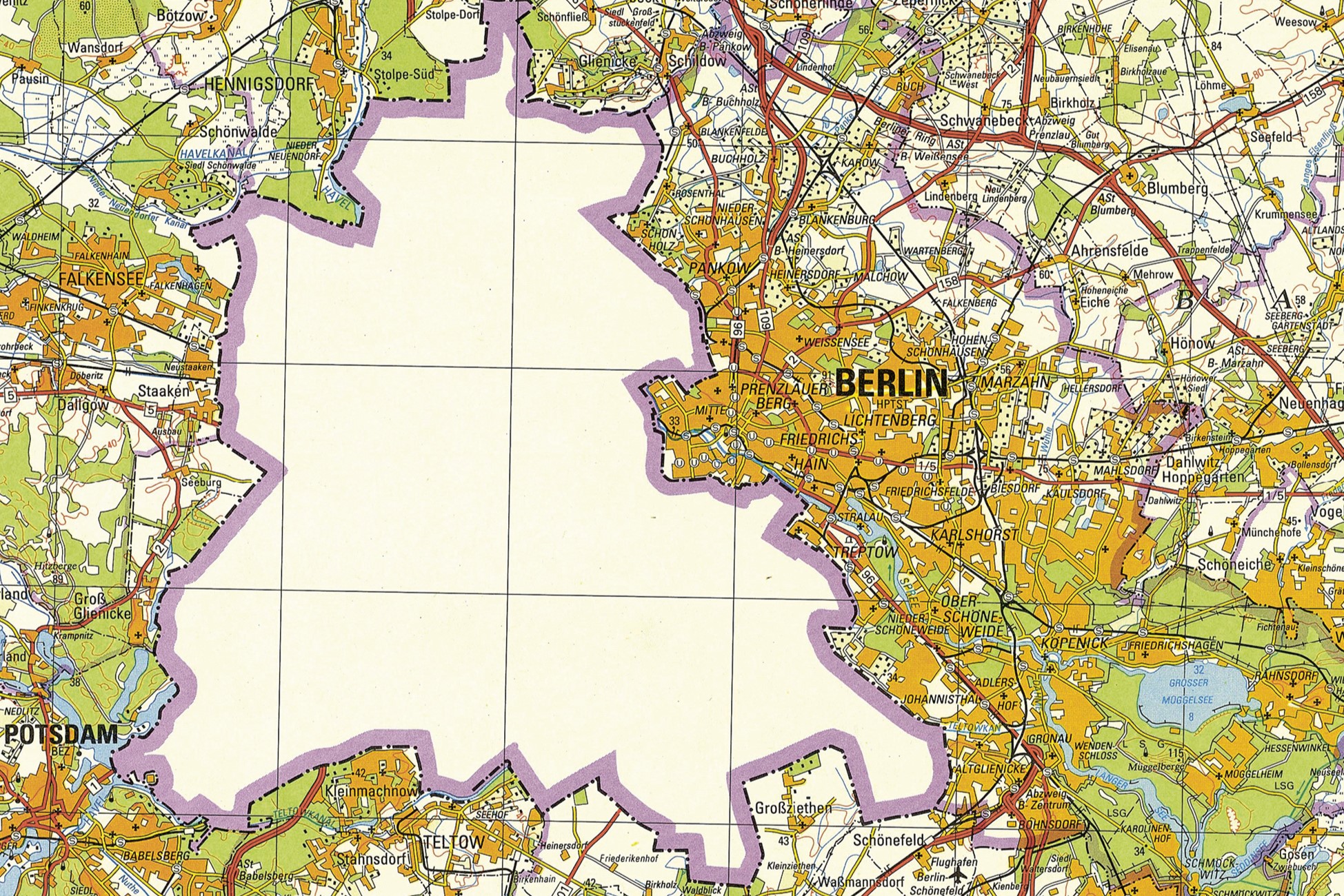

This negative feedback loop makes the relationship between borders and boundaries more difficult to grasp. While borders rely on coercion to shape behavior, boundaries reveal the degree of commitment agents have toward the system’s logic. Perhaps the clearest way to understand the limitations of borders in shaping social boundaries is by examining cities that have undergone both division and unification.

end of box

Berlin

underline

On 9 November 1989, five days after half a million people gathered in East Berlin for a mass protest, the Berlin Wall dividing communist East Germany from West Germany crumbled. It marked not only the collapse of a physical border, but also the impending demise of the communist bloc as a political system.

While few regretted the dissolution of the German Democratic Republic, for many East Germans, the unification process felt abrupt. Many believed in the socialist way of life and were overwhelmed by the sudden takeover of capitalism. In this case, the lifting of borders had limited impact on the deep cultural, demographic, and economic disparities between East and West. While communism failed as a political system, socialism remains a compelling ideology—still in search of better hardware.

end ofbox

Jerusalem

underline

Another example of a city shaped by borders and wars is Jerusalem. Like Berlin, Jerusalem was administered by two nation-states—Jordan and Israel—from 1948 to 1967. Unlike Berlin, however, Jerusalem was not liberated by a popular movement, but occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War. Population displacement occurred during both wars: in 1948, Palestinians fled to East Jerusalem while Jews fled to the West.

When the city was “unified,” Jewish residents were permitted to reclaim property in East Jerusalem, while Palestinians were not allowed to reclaim their property in the West. Jerusalem is another example of the dependency of borders on boundaries. In this case, the physical borders lifted after the war were replaced by new forms of division—namely, property laws—driven by the logic of geopolitical conflict and reinforced by a framework of Jewish supremacy.

end ofbox

A logic reaching its end

underline

The proliferation of walls and physical borders between nation-states in recent years indicates that the self-evidencing power of national borders is eroding. There is a growing gap between nation-states’ ability to apply their internal logic to organize the sociopolitical environment and their capacity to remain coherent. While most social phenomena are complex and relational, three key factors underpin this dynamic and can be highlighted:

First, the logic of nation-states does not account for the parameter of flow. It assumes a static world made up of discrete, self-contained entities—like islands—each with a unique ‘self.’ Today, this logic falls far short of being a good regulator of the social environment.

Second, the boundaries of nation-states—based on their monopoly over force—are ineffective against phenomena indifferent to such limits, like viruses, pollution, or the spread of ideas and information. As a result, neither physical borders nor national frameworks help us grasp the causal structure of today’s social environment.

Third, nation-state's citizenship assume that place of birth—and by extension, parentage—predicts an agent’s loyalty to the State. Given the points above, this assumption is at best questionable, and at worst invalid. Without a reliable way to anticipate alignment, citizenship loses its effectiveness as a tool for creating a stable and expectable social environment.

When effective, nation-state borders and boundaries helped create and sustain a sparsely coupled social environment, where the causal structure of events was relatively clear. The growing sense of chaos experienced by many—especially in liberal democracies—can be understood as a condition of dense coupling, where too many things are interconnected without clear insight into causes or the consequences of actions.

end of box

Let there be ____________?

underline

Ineffective social boundaries are felt across social systems and compel agents to revisit and redesign the rules that define them. Recognizing a feedback loop that can serve as a new boundary is no easy task. Existing systems—and their boundaries—are more visible, making them easier for agents to infer and interpret. But how can we recognize an emerging boundary? How can we distinguish, among the many new and shiny initiatives, the ones that carry the promise of a new feedback loop—one capable of attracting attention and commitment, and potentially defining the boundary of a new social system?

It may sound simplistic—or even naïve—but from my perspective, recognizing potential feedback loops depends on our ability to identify the “good things” in our environment and to discern what makes them good. This is not a new method for recognizing emerging forms of social organization. In fact, my first encounter with this technique came from my community’s story of how 'things began' (see below).

The described transition from chaos to order is a speech act, not a literal account of events, however foundational texts like this can serve as tools for marking and delineating social boundaries—both between systems with similar temporal depth (e.g., other religions) and those with different temporal depths (e.g., nations, states).

It’s important to note that boundaries are ours to imagine and commit to. They do not mark the beginning or end of a social system; rather, they delineate an abstract and intelligible ‘self’—the best-case scenario of that system. Paying attention to what appears good, and understanding what sets it apart, offers a practical toolkit for guiding action in times of transition—when one system fades and another has yet to fully emerge.

end of box

A toolkit for system's creators

underline

Maintain relational cohesion: A good boundary doesn’t dilute an existing one—it upgrades it. The rule of God and monarchies was replaced by the rule of law—not to end civilization, but to reduce arbitrary governance. Scan your social environment and try to define the source of arbitrariness and surprise in a single word. This will make it easier to identify a feedback loop that does not rely on it.

Increase temporal depth: When faced with uncertainty in the social environment, we tend to focus on short-term goals and local optimization. Our capacity to imagine alternatives shrinks, and we become preoccupied with proving that we’re the "good" ones. Let that go. When the social systems we’re embedded in become dysfunctional, it’s a sign that we’re all—at least partially—getting it wrong. Instead, try to recognize the gaps in belief, information, and knowledge that prevent long-term thinking. Use those gaps to set goals that extend beyond the time horizon of the current system.

Resist disintegration: Don’t cave to the urge to dismantle existing systems or abandon familiar forms of social organization in an attempt to “start over” or “go back.” Communist Russia exemplifies the “start over” approach. That case shows how such a move often leads to the irreversible destruction of societal temporal depth—families, tribes, unions, nations, and religions built through years of social interaction. Make America Great Again is another example that reflects the desire to "go back." But social systems follow the arrow of time: they can collapse, but they cannot be reverted to earlier versions of themselves. Trust the process. Self-organization is a process of reiteration—a search for states of 'liveliness' with enough vibrency to sustain life and enough stability to improve upon early versions.

Communicate: If you believe you’ve identified the source of surprise in our current system—if you’ve found initiatives that use a different feedback loop, harness agents’ commitments, and set goals on a deeper temporal scale—share your findings. If you've located or built initiatives that lean on existing systems but can operate independently of them, communicate that too. You may be surprised by the synergies such an investigation can yield when undertaken collectively.

end ofbox

To sum up

underline

Borders make us feel like our world is ordered and manageable. Boundaries maintain the internal coherence of our social systems and reveal their capacity to organize the social environment according to their logic. At their core, however, the boundaries of social systems reflect our ability to create a conceptual separation between our system(s) and the broader environment.

The value of such a conceptual separation lies in its ability to reduce disorder and uncertainty within the social system, compared to the surrounding environment.

Since all social systems are fictional approximations—reflections of our best understanding of the world at a given point in time—there is no reason to become overly attached to them, nor to fear their re-creation. Social systems are meant to help us better understand our environment and engage with it more effectively. They enable us to relate to ourselves and others in meaningful ways.

There are many ways to feel lost in uncertain times, and just as many ways to notice something new taking shape. The simplest is this: “Let there be ______.” Whatever you hope to see, imagine it already exists. Notice it. Then, look for the good in it. See early, imperfect beginnings not as failures but as signs of growth. And when you find something good around you, pay attention to what makes it stand out.